Article Written by Nick Curcione

Ask practically anyone who fishes for fun to recall their most exciting moments on the water, and they’ll most likely recall an instance of what anglers simply refer to as a surface strike, that all too brief time span when a highly aroused predator bolts from below to devour your offering. Whether it’s a palm sized panfish or a striped marlin, the sensation of a fish disturbing the surface in pursuit of a top water meal is an event that will light up your emotional circuits. It’s the type of encounter that has bred legions of specialized anglers like trout aficionados who will only fish with dry fly flies and bass devotees preoccupied with top water artificials.

Most of us in the angling world do not become so narrowly focused and come to terms with the fact that the most consistent action is going to take place somewhere below the surface. For fly fishers this means that you must get your fly down. If you don’t have to present it too deep, maybe only a few feet or so, a floating line with an appropriate leader is all you need. Fishing shallow water flats for species as diverse as bonefish or carp are typical examples. But when the game changes and you need to present a fly somewhere in the depths, be it fresh or salt, you’ll need a sinking line designed explicitly for that purpose.

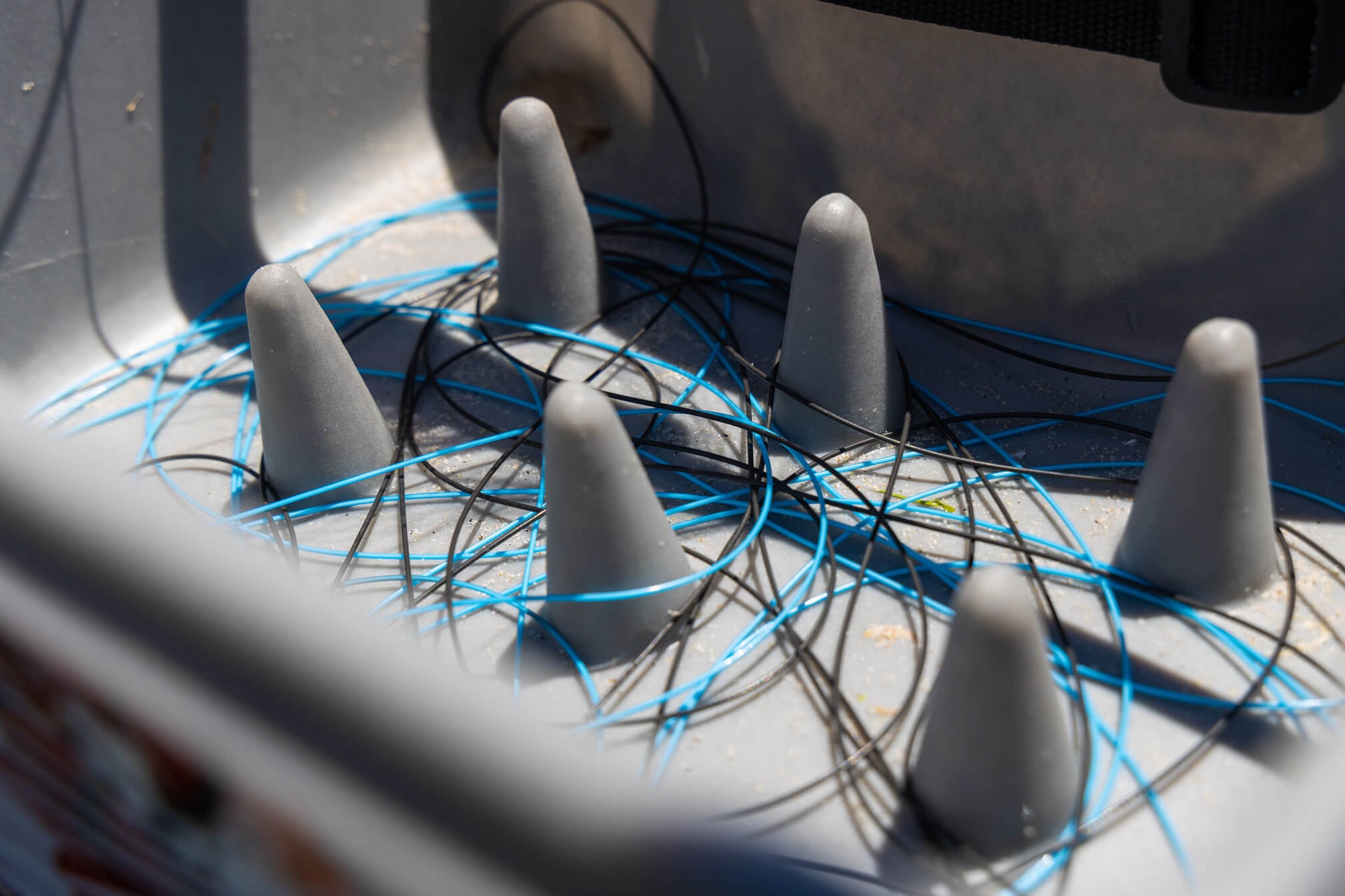

Early on in my fly- fishing career nearly 50-years ago, sinking fly lines were not so readily available. The go to line for that purpose was lead-core. But today you have an abundance of choices. Browse Cortland’s website and you’ll see there’s a fly line for just about any given set of circumstances. My two favorites for sinking applications are the Compact Sink and the Striped Bass Sink. Both lines feature 28-foot sinking head sections, and this shortened length makes the casting sequence considerably easier. If you are new to the sport and just learning to fly cast I recommend starting out with a floating line. With their larger diameters and brighter colors, they are more visible, and their velocity is also a tad slower making it easier to learn proper loop formation and control.

Unfortunately, many fly fishers quickly become disenchanted with sinking lines primarily because they have difficulty casting them. But it’s not the line’s fault. If someone casts poorly with a floating line, switching to a sinking line will not improve results. However, if you are proficient with floating lines the skill set will readily transfer to sinking line applications.

This may seem obvious but the first point to bear in mind when giving sinking lines a try, is the fact that unlike floaters they cannot simply be lifted off the surface. A proficient caster will easily be able to pick up 35-feet or more of floating line from the surface, make a back cast, and shoot yards more line on the forward cast. If there’s one main disadvantage of a sinking line, it’s the fact that a significant length of line cannot be plucked off the surface. Any line that is outside the rod tip is going to slip below the surface and before you can get any line out to the target area, it must be brought back to the surface. Some lines sink the entire length of the line, while others have a sinking head section and are referred to as integrated lines. To prepare for a final forward cast a portion of the head section will have to be coaxed back to the surface and this is simply executed by means of a roll cast. Depending on the line’s sink rate and the length of the head that’s sunk below the surface one or two roll casts may be necessary to bring the entire head section on the surface. The casting sequence that begins with a back cast followed by a forward cast can only be made once the head section is lying on the surface. With the head on the surface, immediately make the back cast and then the forward cast.

If you wait too long the head will sink and you will have to roll cast it back to the surface. As noted above, because sinking lines tend to have smaller diameters than floaters they will travel faster. To accommodate this added velocity, you want to slow down your casting stroke. Most casters, even those who rate themselves as accomplished, put more power into their strokes than necessary. And particularly with sinking lines you want to make the easiest back casts and forward casts possible. A good rule of thumb is to try and cast lazy. Folks who use violent strokes like they’re trying to ward off an incoming wasp do not achieve efficient results. When casting any fly line, it helps to bear in mind that the line is going to make an abrupt 180-degree transition from the back cast to the forward cast and things are going to be even faster with a sinking line. You don’t want to add to this by making an all too powerful casting stroke.

A second imperative is to avoid excessive false casts. False casting wastes time and energy and in most cases is a result of poor casting technique. Particularly with sinking lines, if you start making false casts the timing of the back casts and forward casts become difficult to control and the result is typically not what you were aiming for. Ideally once the head section is brought to the surface, there should only be two roll casts to get the entire head section to the surface followed by a back cast and forward cast. Here is the sequence.

Strip in line to a point where you have at least a few feet of the head inside the rod. Make a roll cast to bring the remaining portion of the head to the surface. If need be, make a second roll cast to get the entire head section outside the rod tip. Rather than ripping the line from the water by immediately bending the elbow, draw the line to you by pulling the rod toward you and slide the line across the surface. Elevate your arm slightly as you draw it back and make an easy back cast by the forward cast. Experience will dictate how much line you can extend outside the rod tip for the forward cast but as a rule of thumb the entire head followed by 1 to 5-feet of the level section of running line is what you will need to make the cast.

A prerequisite for casting these lines is knowing how to double haul. Instead of trying to put all your power into the forward stroke, a sharp haul (tug) on the line during the forward cast is the key to achieving added distance.

If you are willing to give them a shot, you’ll find that sinking lines can significantly open a whole new spectrum of fishing opportunities. Even in shallow water situations these lines can prove invaluable. In salt water you frequently must deal with strong tidal currents where getting a fly only a few feet deep can be difficult without a sinking line. For example, sinking lines have been my primary choice for corbina fishing in the Southern California surf. Similarly on many occasions pursuing shallow water stripers in the northeast, sinking lines proved the hot ticket delivering flies to bass that were foraging prey like sand eels and crabs off the bottom. Any time you must plumb the depths but still want to use fly gear, there’s only one way to get down, connect with a sinking line.

About the Author

In addition to his former 35-year career as a university professor, Nick is an internationally recognized outdoor writer, instructor, lecturer and tackle consultant with a lifetime of angling experience. He is truly an ambassador for sport of fly fishing. Nick is especially noted for his casting expertise and instructional clinics and is one of the country’s leading authorities on sinking lines and shooting heads. He is recognized as one of the pioneers in the use of double-handed rods in saltwater. In 2011 he received the IFFF Silver King award for his contributions to saltwater fly-fishing.

Nick has been on the sport fishing show circuit for more than 40 years, where he has been a featured attraction for productions like the International Sportsmen Expositions, The Great Western Fishing and Hunting Shows, Marriott’s Fly- Fishing Fairs, the Shallow Water Expositions and The Fly-Fishing Show.

His fishing travels have taken him to a variety of locales, including all the coastal waters of the continental U.S., Alaska, Canada, the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America, New Guinea and the South Pacific.

His writing credits have been extensive, with numerous articles in local, national and international publications. He has authored four fly fishing books, The Orvis Guide to Saltwater Fly Fishing, Baja on The Fly, Tug-O-War, A Fly Fishers Game and The Saltwater Edge.

Over the years Nick has served as a consultant for several major tackle companies and is currently working with Cortland Line and Thomas and Thomas fly rods.